A buzzer goes off in a large industrial kitchen at an Army base in Natick, Massachusetts. Two small metal tubes full of food—truffle mac and cheese and hash browns with bacon—have been heating up for five minutes in a steam oven and are now ready for eating. Daniel Nattress, a senior food technologist with the military’s Combat Feeding Division, uses a red protective mitt on his right hand to grab them.

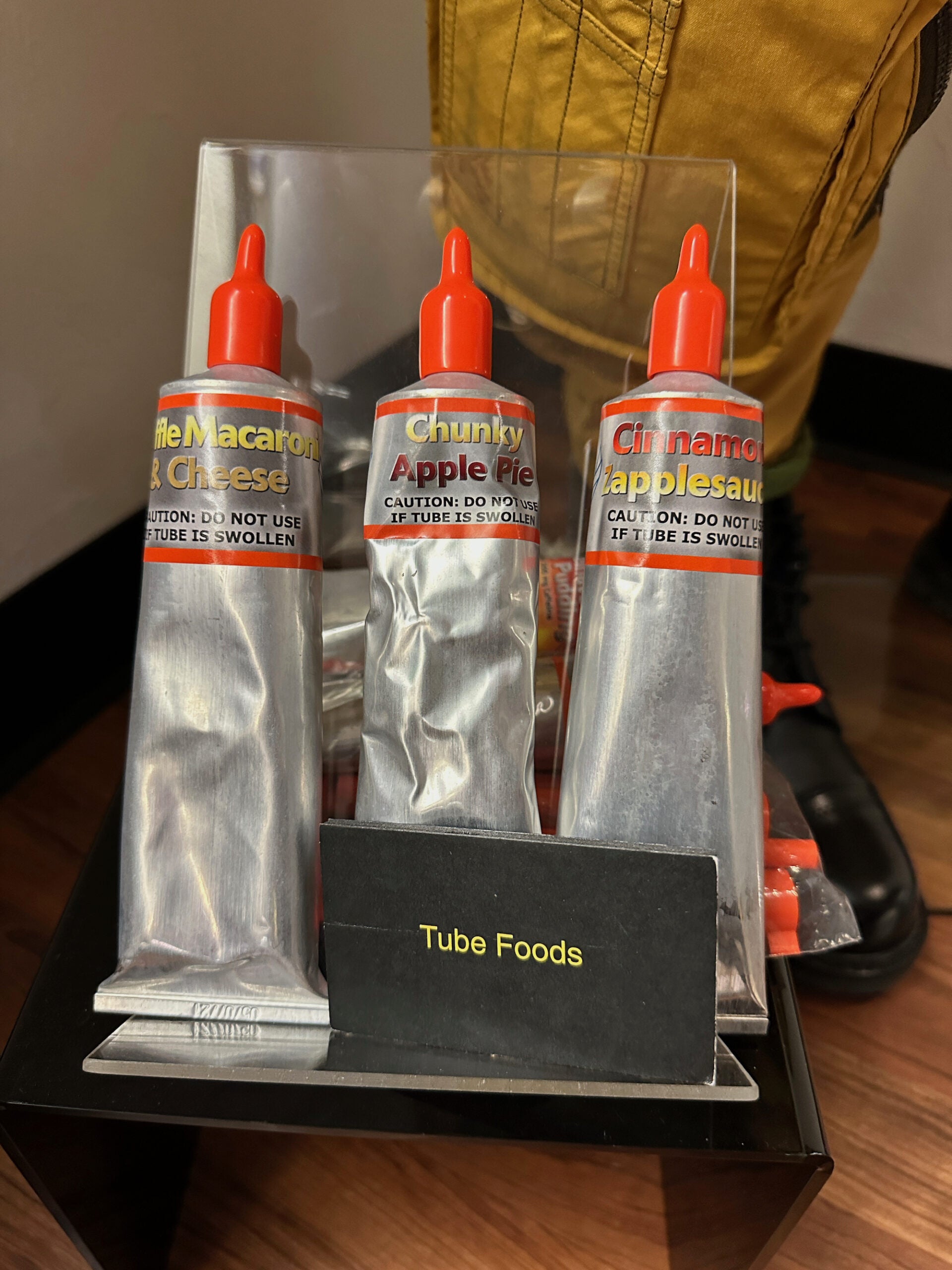

Then comes the moment I’ve been waiting for: a chance to eat the food that comes out of these tubes—the mac and cheese, the hash browns with bacon, and a tube full of what’s called chunky apple pie, which I’ll be consuming at room temperature. The apple pie is first, and attached to the tube is an orange probe that’s like a rigid straw. I squeeze the tube to push the food through the probe, and eat some. “It actually tastes like apple pie,” I remark.

The food made in this facility is unique among military rations for the Department of Defense. A soldier in the field may get their nourishment from an MRE (Meal, Ready-to-Eat), sampling a flavor like “spaghetti with beef and sauce.” Or, if they were at a base, they’d eat whatever was served at the dining facility. Meanwhile, a sailor on a ship or submarine will eat grub in the galley. But the pilots of the high-flying U-2 spy planes bring along sealed tubes of food to give them a boost during a long flight. Here’s why they rely on tube food, and how it’s made.

Dining at 70,000 feet

When an Air Force pilot flies a U-2 aircraft, they wear a full pressure suit and helmet. The plane is known for being both a challenge to fly—especially to land—and for its ability to soar at heights significantly higher than commercial airliner cruising altitudes. The U-2 can operate, according to an Air Force fact sheet, “at altitudes over 70,000 [feet],” and the suit the aviators wear exists to protect them.

“Really what it does is it acts as a backup envelope, as it were, for the pilot if the cockpit cabin were to decompress,” says Hannah Jacobs, the Air Force program manager at the David Clark Company in Worcester, Massachusetts, which makes the suits. It’s like “a secondary atmosphere—a container to keep the individual flying the aircraft safe if the aircraft were to become damaged, or if the cabin pressurization system were to fail,” she says.

Jacobs knows the topic well. Before working for the David Clark Company, she was in the Air Force, where she was a technician who was a part of the U-2 program, focused on areas such as maintenance and repair of those pressure suits.

[Related: The real star of this aerial selfie isn’t the balloon—it’s the U-2 spy plane]

Someone wearing a sealed pressure suit can’t exactly grab a protein bar to gnaw on if they get hungry. That’s where the tube food and the straw-like probe comes into play. The pilot, who can heat the tube in the cockpit, puts the probe through a small portal in the helmet, allowing them to get sustenance while staying protected within the envelope of the sealed suit. “The idea is that you don’t have to break the seal at all,” she says. “The straw goes in through the feeding port, and that also has an o-ring around it that would prevent any kind of air leakage from escaping the suit, and so you stay protected the entire time.”

While there are 19 flavors of the tube foods, she recalls the popularity of the chocolate pudding (there is both a regular version and a caffeinated one) and that she once, while in the Air Force, “experienced a chocolate pudding shortage.”

“You never want to be the tech delivering that news to anyone—that the chocolate pudding supply has been exhausted,” she adds.

How the tube food is made

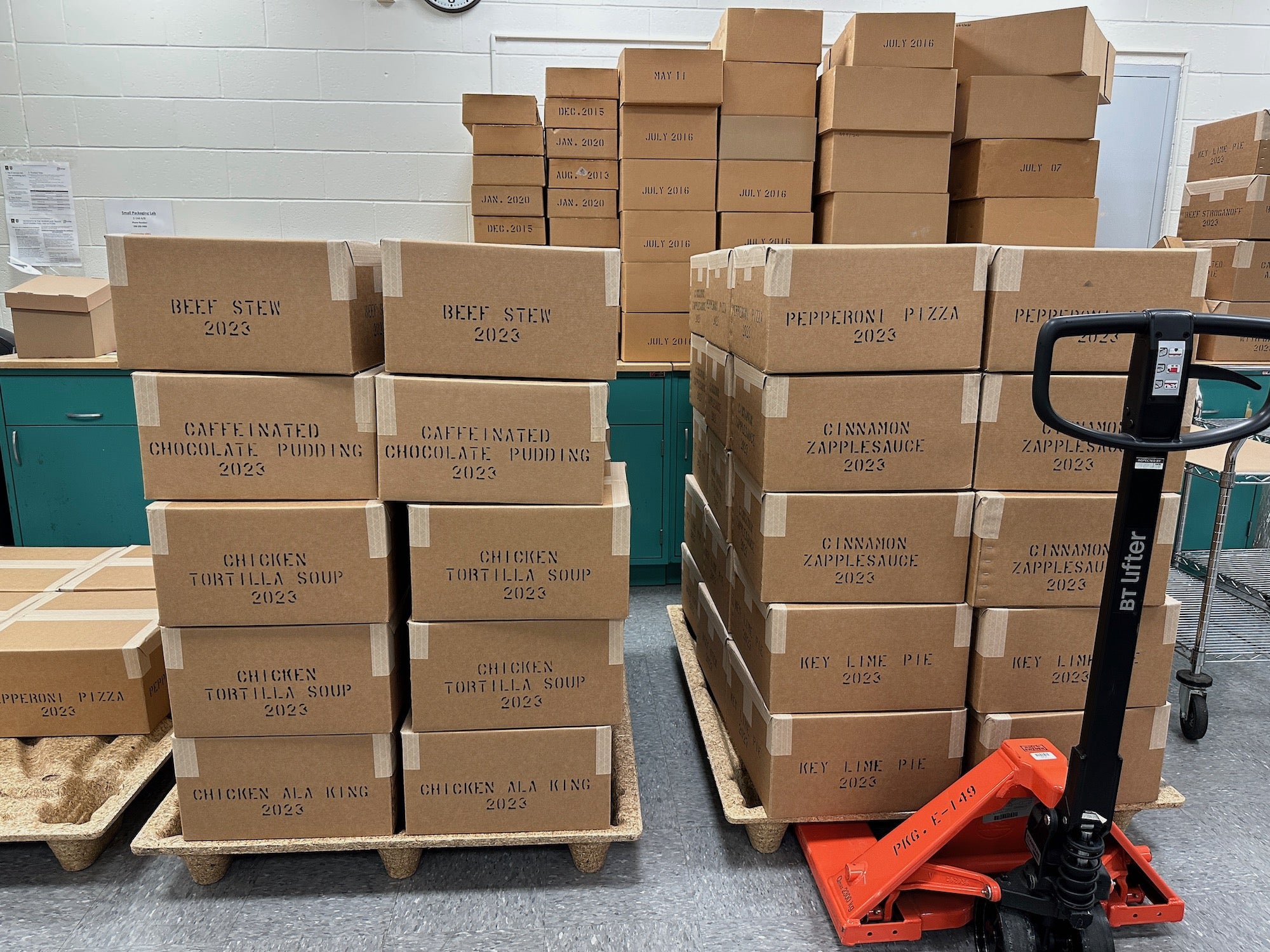

The food that a U-2 pilot eats—flavors include hash browns with bacon bits, chocolate pudding, chicken tortilla soup, polenta with cheese and bacon, beef stroganoff, beef stew, and pepperoni pizza—begins its life in the Department of Defense kitchen in Massachusetts. (Technically in a building called the Bainbridge Combat Feeding Laboratory, at the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Soldier Center, which is also known as the DEVCOM Soldier Center, which is located at a base in Natick.) Favorite items include pears, chicken tortilla soup, and the hash browns with bacon.

The main event happens at the Nordenmatic 602, a machine that according to the company’s website can fill various kinds of tubes with various kinds of things—think stuff like toothpaste or cosmetics.

[Related: I flew in an F-16 with the Air Force and oh boy did it go poorly]

The tubes for this Air Force cuisine are made of aluminum with a gold food-grade liner inside to prevent the grub from being in direct contact with the aluminum. Each one holds about 5 ounces, and before it’s filled with its delicious contents, one end remains open, so it’s essentially a cylinder. The tubes take a trip on a small track in the machine with their open end facing upwards, passing below a hopper from which the food travels down into the tube. Another part of the machine then crimps the end of the filled tube, sealing it.

“This is brand-new,” Nattress says, noting that it replaced an older machine. So why the upgraded equipment? “They’re envisioning that the U-2 will fly another 20 years,” he says. Two more decades of flight for this storied aircraft means two more decades of tube food production.

To get into the hopper above the Nordenmatic, the food travels through a hose from a 40-gallon steam-jacketed kettle. This large metal container is where the food is mixed—it then gets pumped into the hopper of the nearby Nordenmatic machine. After being filled, the tubes are sterilized in a retort oven.

It’s better than baby food

Nattress, who has been in charge of the tube food program for 25 years and is a trained taste-tester, takes the culinary mission seriously. He notes the four ways that people derive sensation from food: taste, texture, smell, and appearance. A pilot who is squirting the food directly from an opaque tube through a probe and into their mouth is missing out on some of those senses, leaving two for them to focus on.

“Texture and taste are huge,” he says. The key is to make sure there is a texture to the cuisine, with little particles that can fit through the probe.

“If we just grind it down into nothing, you lose that texture,” he says. “You want to have a little bit of texture in there, so that they can discern the food particles.” For example, the chunky apple pie dish is made from real sliced apples (as opposed to applesauce) that have been ground up, along with graham cracker crumbs. The chunks are good, but they can’t be too big. “Imagine being up there at 70,000 feet, and you want to have something, and it clogs up,” he says.

While holding a tube of the chunky apple pie, he recalls the process that went into developing that flavor. “We’ll take a nice apple pie—a nice, good-quality apple pie—we’ll put it in our mouth and taste it, and we try to describe, write down, those sensations that we get. And we try to recreate that in here,” he says, pointing at the tube.

In other words, this stuff is not just flavored paste, sauce, or a baby-food like substance. “Even like the more advanced baby foods, they may have a little bit of texture, but they don’t have a lot of spice in it,” he adds. “We want to have that full-flavor profile.”

Eating the tube food

The chunky apple pie I tasted straight from the probe included not just apples, graham crackers crumbs, but also cinnamon, nutmeg, and “some dairy,” Nattress says. After eating the dessert item first, it was time to eat the two that he’d heated: the truffle mac and cheese, and the hash browns with bacon.

To conserve those plastic probes, he squirts the truffle mac and cheese straight onto a plate into a gooey yellow pile, and hands it to me with a spoon. This item’s ingredients include truffle oil, gouda, a cheese powder, onion powder, paprika, little bitty pastas, and cream.

The next one was the hash browns and bacon, whose origin story, Nattress says, involved a request for breakfast food. “They were expecting an egg product,” he says. But that’s not what they got—they got a delicious and savory combination of hash browns and bacon bits. He squirts that one onto a different plate. The hash browns, he says, have actually started out as tater tots.

I tried both, and perhaps due to an aversion for creamy food, the winner in my eyes was the hash browns with bacon. “I think this is my favorite, so far,” I say, after my first spoonful of this breakfast item made for spy plane pilots. “You can taste the little bacon bits in there.”

Nattress says they produce more than 20,000 tubes each year.

Watch a short video about the process below—including the taste tests.

The post Inside the US military lab that makes tube food for spy plane pilots appeared first on Popular Science.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

from | Popular Science https://ift.tt/BevRA4m

0 Comments