From cities in the sky to robot butlers, futuristic visions fill the history of PopSci. In the Are we there yet? column we check in on progress towards our most ambitious promises. Read the series and explore all our 150th anniversary coverage here.

In 1953, dozens of teens at Brooklyn High School for Automotive Trades took one of the first-ever realistic driving simulators out for a spin. The Drivotrainer was no Gran Turismo, but it offered road video and a bumper car-style driver’s seat with a steering wheel, clutch, brake, mirrors, speedometer, and even a hood ornament.

When Popular Science covered the Drivotrainer’s Brooklyn, NY debut in May 1953, teen driving accident rates in the US were skyrocketing, blamed largely on an increase in automobile access and lack of adequate training. For the 15–24 age group, motor vehicle death rates had surged over the prior decade, more than doubling by 1956 to nearly 43 per 100,000. But it was too costly for schools to provide enough dual-control training cars and instructors to meet the increased driver-education demand. Since flight simulators, which were first introduced as early as 1910, helped prepare pilots for real-world flying, traffic safety experts hoped that driving simulators would yield similar results for young drivers and reverse the troubling car-crash trend.

For the unlikely developer of Drivotrainer, Connecticut-based Aetna Casualty and Surety Company (now owned by CVS), driver education and accident prevention was good not only for its bottom line but also for its reputation. Aetna had been investing in driving-simulation technology as far back as 1935, when it introduced its Reactometer to measure driver response time. The Reactometer was followed by the Steerometer and then the Driverometer, an arcade-style machine that offered motion pictures to simulate driving conditions.

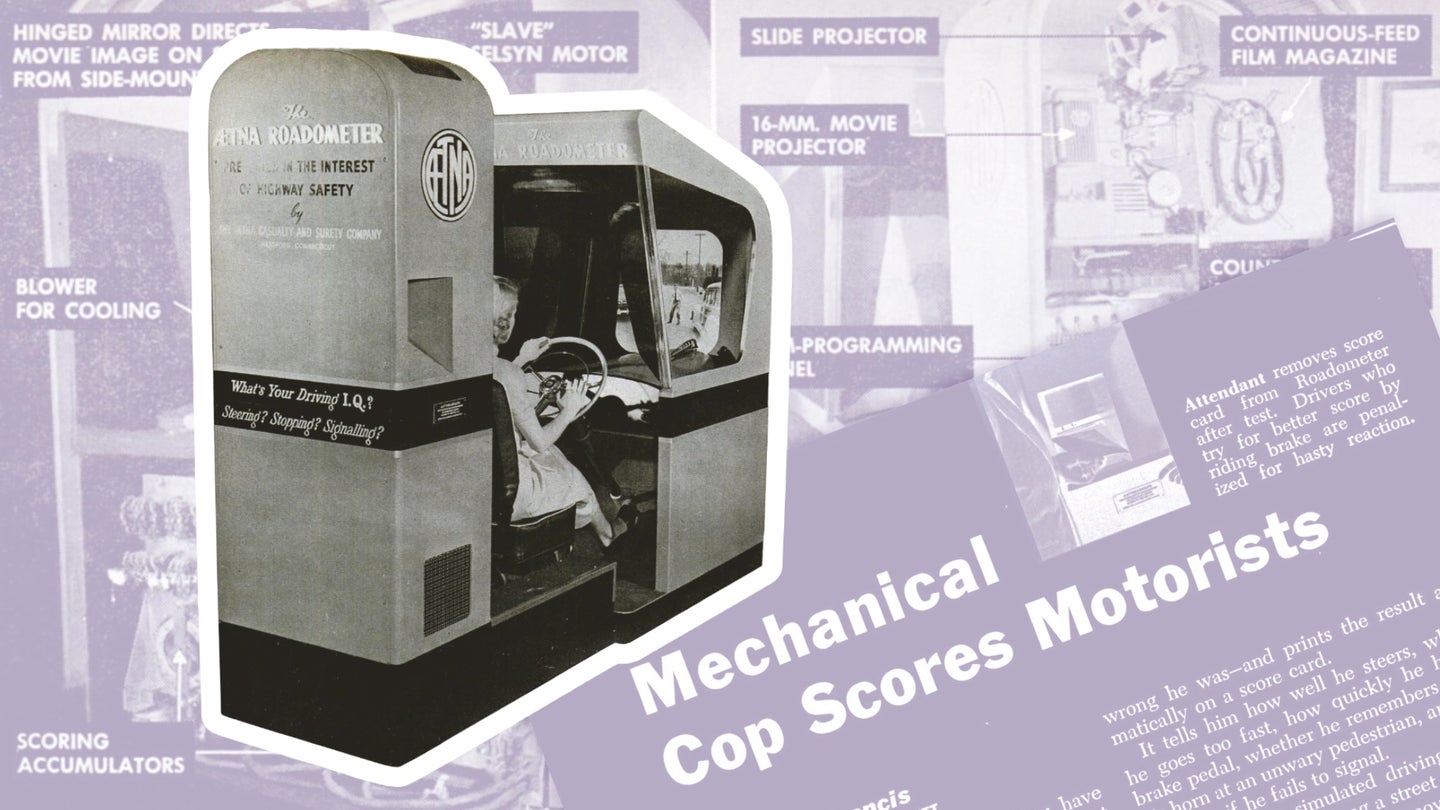

In May 1951, Popular Science featured Aetna’s next generation simulator, the Roadometer, a driving test that employed video and a booth-like car seat. The Drivotrainer, designed for classroom training, improved upon the Roadometer’s design by automating scoring and separating the video from the booth, enabling it to be projected on a large screen for a room full of students seated behind the wheels of Aetnacars. Success, however, could only be measured by how well simulator-trained drivers performed on the road relative to their untrained and road-trained peers. Aetna needed proof of simulation training’s positive impact.

Positive transfer of training is a concept based on developmental psychologist Jean Piaget’s theories of cognitive development, published in numerous works between the 1920s and 1940s. Specifically, the law of assimilation proposes that we tend to respond to new situations in ways that are similar to familiar situations. The idea of a driving simulator is to familiarize students with driving fundamentals and challenging traffic scenarios before they take to the road.

“We can put people in scenarios that they may never experience and make them aware of the risks and dangers [of driving],” Eric Jackson, Executive Director of the Connecticut Transportation Institute (CTI), a research center at the University of Connecticut, tells PopSci. In addition to compiling car crash data to track trends, Jackson’s team operates a variety of driving simulators to study driver behavior under different conditions such as when a driver is impaired or distracted. CTI’s simulator collection includes a car mounted on actuators with a surround screen, and several motorcycle simulators. They also use desktop and virtual reality simulators.

According to researchers from Sweden, who used a driving simulator test in 2023 to complement on-road testing, simulators are an effective way to test drivers in unusual hazardous situations, as Jackson suggests. Their simulator tests put drivers in scenarios too risky for road tests and successfully flagged deficient driver reactions.

The six-week Drivotrainer course at the High School for Automotive Trades—a vocational school that still stands on Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn, NY’s Greenpoint neighborhood—was one of several Aetna-sponsored driving simulator trials conducted around the US in the 1950s. Others included students from William Cullen Bryant High School in Queens, NY; Iowa State Teachers College (now the University of Northern Iowa); and Hollywood High School in Los Angeles, CA. At the time, the American Automobile Association (AAA) had developed its own driving simulator, the Auto Trainer, which was trialed at Anacostia High School in Washington, DC, and in Springfield, PA.

A 1960 report by the National Commission on Safety Education analyzed the Drivotrainer and Auto Trainer trials and concluded that “some transfer of learning occurs when [driving simulators] are used.” But the report also noted significant gaps in the available performance data and called for additional testing. Looking to the future, however, the authors added, “recent developments in psychological theory view the operator as an integral part of a man-machine system, and may well point the way toward increasing significantly the transfer effects of simulator teaching.”

Jackson believes that simulation does help rewire the brain to think about what could happen on the road. He noted that simulation technology today, including graphics, sound, and tactile sensors can make the experience ultra-realistic. “As part of our scenarios,” he explained, “we’ll have a kid chase a ball in front of the car. Even in the simulator you get that same feeling of, ‘Oh my God, I just about hit a kid.’ You never want to experience that in real life.”

After a simulation-training surge in the 1950s and ‘60s, which included Drivotrainer exports to other countries like Great Britain and Sweden, driving simulator tech did not advance much and its use faded, although Aetnacars could still be found in some driver ed classrooms into the 1990s. Even as the US steered away from driving simulator classes for teens, they remained commonplace in parts of Europe, and companies that employ commercial drivers or certify them have continued to rely on driving simulators, even in the US.

But driving simulators for young drivers appear to be on the rise again in the US and across the globe, thanks to technological advances that have improved capabilities and reduced costs. Companies like Virtual Driver Interactive, Greenlight Simulation, and Drive Square offer immersive driving experiences that include combinations of surround monitors, virtual reality headsets, sound, and even full or partial vehicles mounted on motion platforms. Video game developers have been getting in on the action, too, offering families a home-based experience. Valve Corporation offers Virtual Driving School for its popular Steam platform. And Driving XE offers Driving Essentials for Playstation and Xbox.

Still, not all driving simulators are created equal. In a systemic review of driving simulator trials, researchers from Australia and New Zealand examined simulator fidelity—how accurately a simulator represents real-world driving. They concluded that most trials don’t include enough evidence to validate how well simulators compare to real-world driving, but they noted that significant advancements in simulator technology have led to a “wide variability in simulator design.”

According to Jackson, full-scale driving simulators like the one his team operates at CTI, offer the most immersive experience. “You’re in a real car,” he explains, “with real buttons. You can have the tactile sense. We even have a subwoofer under the seat so you get the vibrations of an engine.” Virtual reality, he notes, doesn’t offer such a realistic experience, but he thinks VR will have an important role to play in teen driver education because of its price point. Full-scale driving simulators can cost $500,000, but VR might be a few hundred dollars (even less for screen-based video game simulators), which could make driver education affordable again for high schools. Jackson notes that simulators can also help close income equity gaps. “For people who can’t afford a car,” he says, “simulators offer the ability to still have their teen learn how to drive and go through a driver education program.”

If you’re the parent of a teen who is about to take to the road, it might be worth looking at driving simulator training in your area, although your teen won’t receive any official accreditation toward earning a driver’s license. Still, while decades of data show that simulators are no substitute for real-world experience, they do have a positive impact on driving behavior. Plus, simulators today may be realistic enough to have an even greater impact than in the past. But if your teen tries to argue that all their hours logged on Gran Turismo or Super Mario Kart should count, don’t fall for it.

The post Why don’t we use more driving simulators to teach teenage drivers? appeared first on Popular Science.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

from Popular Science https://ift.tt/EftpG6O

0 Comments